Pasta and grains.

Pasta.

Shaped by history, migration, and trade, pasta connects cultures across time and geography.

Pasta-like foods date back over 4,000 years. Ancient Chinese records describe millet-based noodles, while the Greeks and Romans made laganon - flat sheets of dough resembling modern lasagna. The Etruscans and Romans developed early forms of pasta by grinding cereals and mixing them with water to create dough, which was typically baked rather than boiled.

By the 9th century, Arab traders introduced itrīyya, a dried durum wheat pasta, to Sicily. This innovation laid the foundation for dried pasta production, which was well-suited for storage and long journeys. (Contrary to popular belief, Marco Polo did not introduce pasta to Italy.)

Between 1565 and 1815, the Spanish Manila galleons connecting Asia with New Spain (modern-day Mexico) transported Chinese wheat noodles along with silk, porcelain, spices, ivory, and lacquerware to Europe. These exchanges influenced Spanish and Latin American noodle food such as fideos and sopa de fideo, illustrating how pasta-like foods evolved across continents.

By the 14th century, pasta-making guilds were flourishing in Europe, with Genoa, Sicily, and Naples emerging as key centers of production. The Industrial Revolution of the 18th and 19th centuries further expanded pasta manufacturing, making it more affordable and widely available. Italian immigrants later carried their pasta traditions to the Americas, helping to establish pasta as a beloved global staple.

Today, a version of pasta exists in nearly every cuisine, from Italian spaghetti and ravioli to Japanese ramen, Middle Eastern couscous, and Mexican sopa seca.

Some pasta types: shape, dough, and suggestions for sauces, pairing, uses, and wines.

Cooking pasta: basic rules that apply to all types.

1. Use enough water. Pasta needs room to move and cook evenly.

2. Many cooks salt the water (unless there is a medical reason not to add salt). Salting the water helps make more flavourful pasta. It seasons the pasta as it cooks. One-2 tablespoons of salt per large pot of water should be enough (it should taste like the sea). Add salt after the water boils – it dissolves faster.

3. Avoid adding oil to the water. Oil can coat the pasta, preventing sauces from sticking. Instead stir the pasta a few times to prevent sticking.

4. Stir in the first minute because pasta tends to stick together as the starches are released. Stirring at the start prevents clumping.

5. Cook until “al dente” (firm to the bite) to give the best texture and prevent overcooking. Check by tasting a piece about 1-2 minutes before the package time suggests.

6. Keep some pasta water (save: ½ - 1 cup before draining). Starchy pasta water helps thicken and bind sauces, making them silky.

7. Do not rinse the pasta. Rinsing washes away starch, which helps sauce cling. An exception: If making pasta salad, rinse with cold water to stop the cooking and prevent sticking.

8. Finish cooking in the sauce by tossing pasta in the sauce for the last 1-2 minutes to help better absorption of flavours.

If the sauce needs thinning add some of the reserved pasta water

9. Pair the pasta with the sauce. Different pasta shapes hold sauces differently (above).

10. Finish with fresh ingredients. Fresh herbs (e.g., basil, parsley), chili flakes, lemon zest, grated cheese, or olive oil elevate the dish.

Tagliatelle are made with durum wheat refined flour and egg (~300 kcal/100 g). They are dusted with flour to prevent sticking before cooking.

Trofie, a traditional short, twisted pasta (Liguria, Italy), holds sauces well, especially pesto. It is also well-paired with light cheese and cream-based sauces and light tomato-based sauces with shrimp or clams.

Tortelloni, a larger version of tortellini, with ricotta and spinach (or other cheese and vegetable) filling. It is well accompanied by burro e salvia (butter and sage), tomato, cream or walnut sauces.

Whole wheat (unrefined) flour pasta has less calories and more fibre than white (refined wheat) flour pasta. Aim to have less than 100 g (as low as 150 Kcal) per person.

Spaghetti, whole wheat, fresh. Whole wheat pasta has a rich, hearty taste complemented well with butter and sage or olive oil with garlic sauce, bringing out the nutty flavor of whole wheat. Truffle, porcini, mushroom, or cream-based sauces, and tomato-based sauces (marinara or ragù) also pair well with whole wheat pasta.

Pasta can be made with spinach or other vegetables incorporated into the dough. Pastas made from chickpeas, lentils and beans contain more protein, nutrients and fibre that white wheat flour. To wash off any undesired textures, consider rinsing the cooked pasta. In general, legume flour pairs well with the same sauces used with wheat pasta.

Spinach tagliatelle, fresh. This type of pasta pairs well with creamy sauces (alfredo, gorgonzola), butter and sage, or light tomato-based sauces.

Gnocchi (potato pasta) is a soft Italian dumpling made with potatoes, flour, and eggs. Here with a simple onion, tomato, and aubergine sauce.

Couscous, a pasta made from semolina flour, is usually combined with vegetables (here: lentils, peppers, cucumbers), tomatoes, herbs, and cheese or nuts. It is well-complemented with a vinaigrette or lemon-herb dressing.

Pasta examples with their sauces.

Spaghetti cacio e pepe, a typical Roman pasta.

To prepare: dry-toast the black pepper over medium-low heat for 30 seconds, until fragrant and add ¼ cup of pasta water. Add the spaghetti (just before al dente), toss, and add pasta water and grated pecorino Romano (cheese sauce). Add parsley.

Spaghetti ai gamberi crudi. Raw shrimp marinated in olive oil, lemon, and garlic are tossed with pasta for a fresh, delicate seafood flavor (Forte dei Marmi, Italy).

Spaghetti ai gamberi, pomodoro sauce.

Spaghetti allo scoglio (“rock”, referring to coastal waters where shellfish are found) is a classic Italian seafood pasta dish from coastal regions, especially Campania and Tuscany. It typically includes mussels (alle cozze), clams (alle vongole), and sometimes calamari or shrimp with cherry tomatoes, basil, in a light garlic, olive oil, and white wine sauce.

Spaghetti al tartufo (with truffles), an elegant and simple match particularly popular in central Italy. The simplicity of pasta is combined with the rich aroma of black or white truffles. Using butter or olive oil, garlic, and Parmesan or Pecorino cheese enhance the truffle’s depth without overpowering it. (Courtesy J. Redi, Turin.)

Penne pomodoro with Parmesan cheese.

Penne alla siciliana: with zucchini (or eggplant) and creamy tomato sauce.

Ravioli, detail: dressed with fried potato skins, an elegant and modern twist on Italian cooking. (Courtesy J. Redi, Turin).

Polenta.

Fegato alla veneziana with polenta (made from cornmeal). Thin slices of calf’s liver cooked in white wine are accompanied by caramelized onions, served with Polenta and powdered parsley.

Polenta is made from coarsely ground cornmeal. It is easily prepared, cooked slowly with water or broth, transforming into a creamy, porridge-like consistency, or left to set and then grilled, baked, or fried. Naturally gluten-free, polenta is a versatile and nutritious carbohydrate, rich in fiber and essential minerals. It pairs well with cheese, seafood, meats, or vegetables, making it a staple in both rustic and refined dishes.

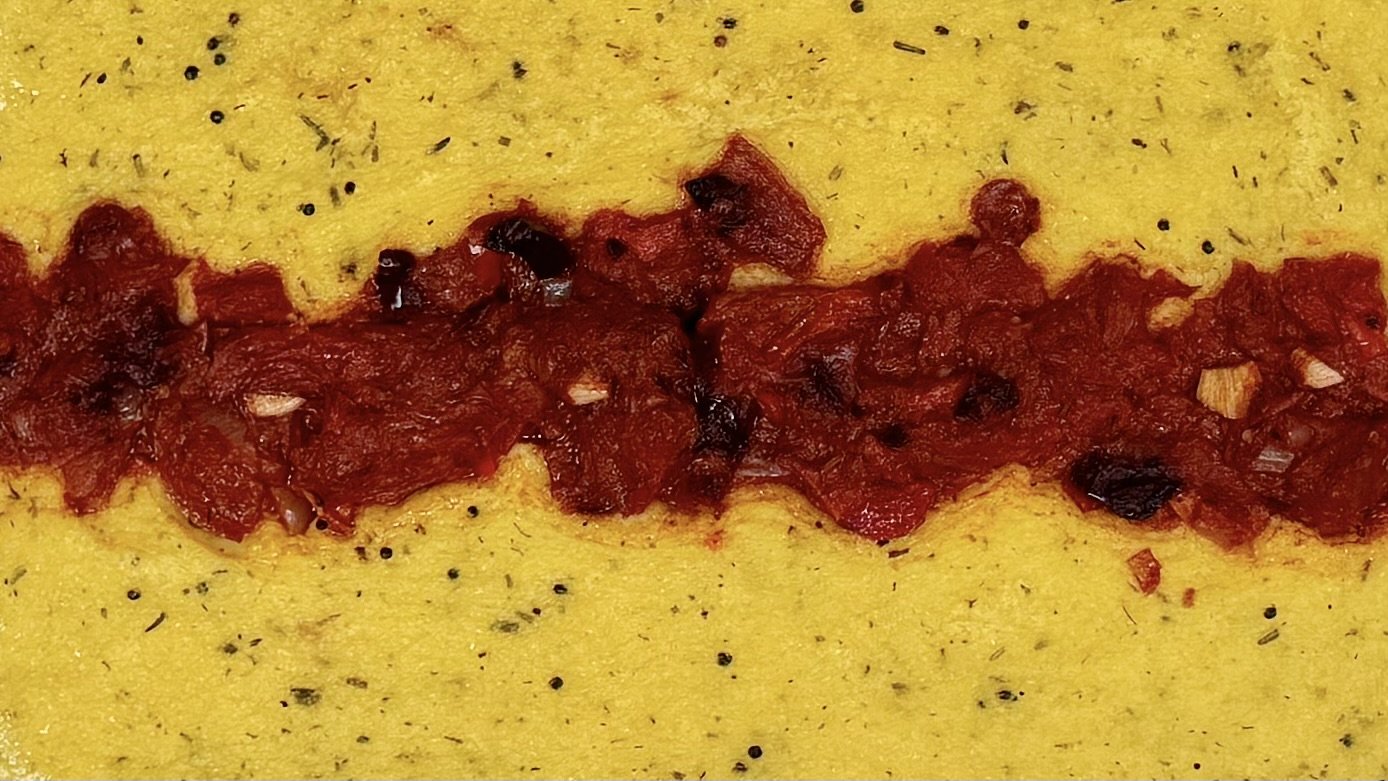

Polenta, grilled. Here, it is garnished with a slow-cooked garlic, onion, tomato, and red pepper sofrito. It can be toasted or fried. Simple and delicious!

Farinata.

Farinata (Genova), a tarte made with chickpea flour, salt and water, is typical of several Mediterranean regions (cecina in Tuscany, fainé in Sardinia, panelle in Sicily, socca in Provence, fainá in South America). Hot and with pepper, it is delicious.

Farinata pairs well with olives, tomatoes, vegetables, cheese, meats, or sardines or anchovies. It is also popular on thin focaccia or pizza.

The rices (arroces, els arrossos).

Paella, an arroz, is a celebrated and popular rice dish from Spain. In this arroz, the rice is infused with seafood flavours.

In los arroces (els arrossos, Catalan), rice is the main character. It is traditionally cooked in a wide, shallow pan. The rice should be tender yet firm to the bite, with a layer of crispy, caramelized rice at the bottom and edges of the pan (the socarrat). Importantly, the rice is not stirred during cooking, allowing it to form this characteristic crust.

Other traditional varieties include paella de conejo (rabbit), with snails and green beans, arròs negre, where cuttlefish and their black ink provide a distinctive color and depth of flavour, and arroz de marisco, typically including combinations of gambas (prawns), mejillones (mussels), almejas (clams), and berberechos (cockles) cooked in a rich seafood stock.