On happiness…

“A multitude of small delights constitutes happiness.”

– Charles Baudelaire

Happiness is in the warmth of human connections.

As humans, our life will inevitably include periods of pain and hardship. Research shows that we can endure these challenges when we have strong relationships. Ultimately, it is the quality of our connections-not whether we are married or single, successful or struggling-that shapes our well-being.

Certain actions can actively enhance our happiness and resilience. By integrating them into our daily lives, we can build a more enduring and meaningful sense of happiness, even in the face of adversity.

Happiness is found in the warmth of human connection, and not in wealth, fame, or status.

By promoting these bonds, we do not just enrich our emotional lives-we extend and enhance the very years we live.

Happiness is more than just a “mood”.

Happiness is linked to strong family bonds, friendships, and meaningful relationships. We are happier, healthier, and live longer by the strength and depth of our human connections, regardless of backgrounds.

Our happiness, health, and longevity are deeply linked to the quality of our relationships.

Enduring happiness is linked to strong family bonds, friendships, and meaningful relationships.

We are happier, healthier, and live longer by the strength and depth of our human connections, regardless of backgrounds.

The Harvard Study of Adult Development.

The Harvard Study of Adult Development sought to answer one of life’s most fundamental questions: what makes us truly happy? It is the longest-running investigation into human flourishing (more than 85 years, spanning several generations, and has data from 1,300 descendants of the original 724 participants). It began enrolling Harvard students in 1938 and later expanded to include Boston’s tenement families (see: Waldinger RJ, Schulz MS. The Good Life: Lessons from the World’s Longest Scientific Study of Happiness. New York: Simon & Schuster; 2023).

It revealed a simple, but fundamental truth: our happiness, health, and longevity are deeply linked to the quality of our relationships.

Nearly 40% of our happiness is influenced by environmental factors, with the remaining determined by genetic variation. Significantly, this means that much of our happiness can be modified.

The link between happiness and health is not merely philosophical but biological. Close relationships provide emotional support, reduce stress, and promote positive mental health. This, in turn, has measurable effects on physical well-being: lower levels of inflammation, improved immune function, and even a reduced risk of heart disease and dementia.

In contrast, chronic loneliness has been shown to be as detrimental to health as smoking or obesity, accelerating cognitive decline and increasing the risk of premature death.

This connection between relationships, happiness, and health naturally extends to longevity-but not just in terms of lifespan. A long life is only meaningful if it is a healthy one.

“Healthspan.”

The Harvard study offers vital insights into “healthspan”—the number of years we live in good health, free from serious illness or disability.

Those with strong social ties not only tend to live longer but also maintain better cognitive function, mobility, and emotional well-being, well into old age. In contrast, social isolation and strained relationships have been linked to faster biological aging, a weakened immune system, and a higher likelihood of chronic diseases.

These findings challenge common assumptions about well-being and success. Political interventions, social programs, and economic policies play relatively minor roles in personal happiness. Instead, fulfilment is found in everyday choices: cherishing a spouse, deepening friendships, engaging with colleagues, and even appreciating small, fleeting interactions, like a conversation with a store clerk or a friendly exchange with a neighbour.

Moreover, the study raises thought-provoking questions about modern life. Social mobility, often seen as a pure good, can inadvertently weaken the very ties that sustain well-being. Moving for better job opportunities might increase wealth, but it can also fragment family connections and disrupt lifelong friendships, undermining happiness in the process. Similarly, while religion’s role in society has waned, its decline may have unintended consequences—faith-based communities, regardless of belief systems, have long provided a sense of belonging, purpose, and mutual support, all of which contribute to well-being and longevity.

Social media.

The Harvard study highlights social media’s dual nature. On one hand, it expands social circles, helps maintain long-distance friendships, and fosters reconnections. On the other, the quality of in-person interactions often suffers, replaced by a superficial and distraction-filled digital existence. Whether this trade-off ultimately enhances or diminishes well-being is a question we may not fully answer for decades—though the study, still ongoing, may one day offer clarity.

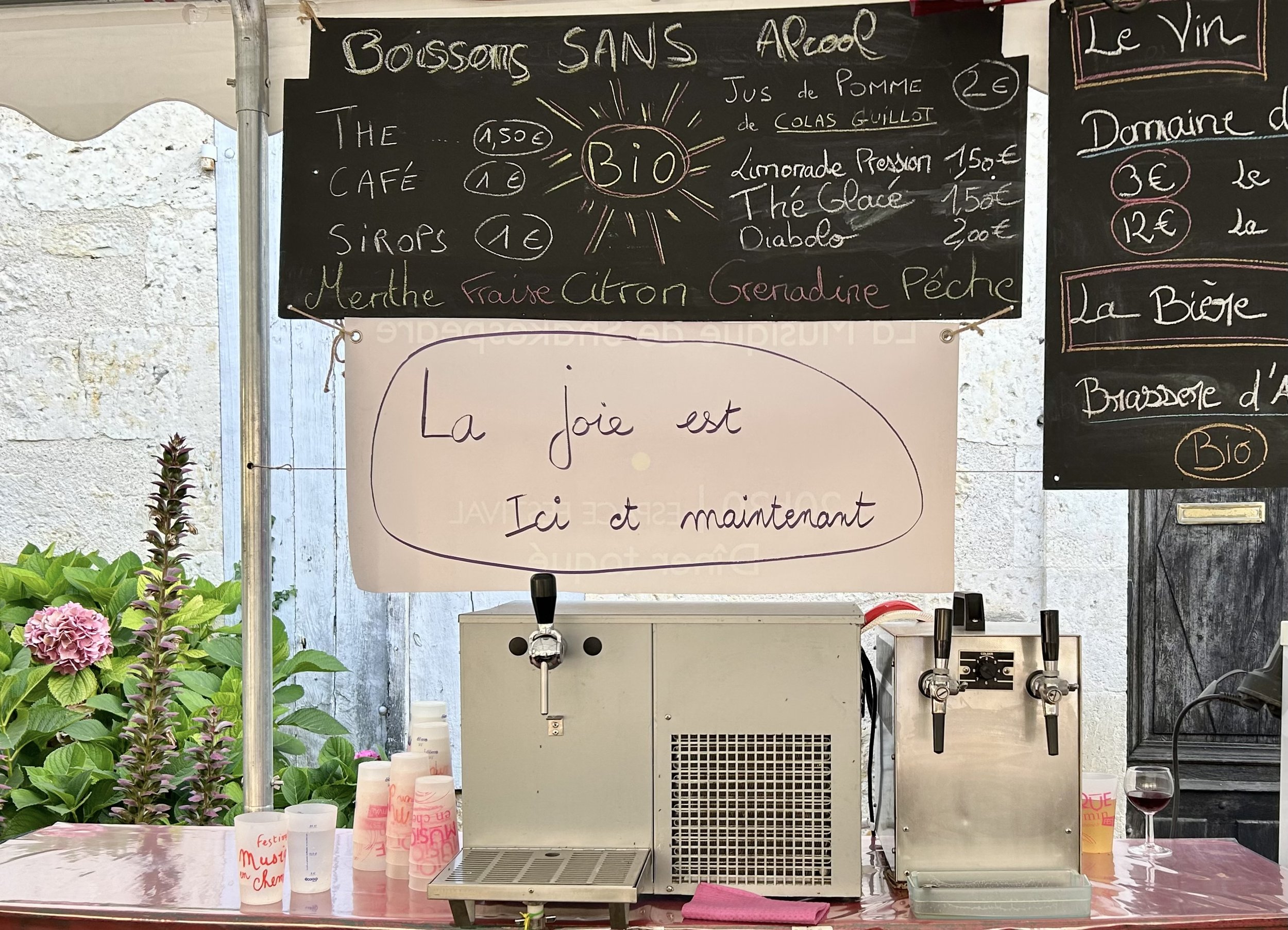

Happiness is here and now.

La joie est ici et maintenant, Joy is here and now. Joy lives in the present moment - not in the past or future. You access it by slowing down, paying mindful attention, accepting life as it is, and practicing gratitude. True joy is not fleeting; it’s a way of being that arises when you are open and fully present. (Beverage stand, La Romieu, France.)

Happiness is like a muscle: it is strengthened and cultivated through intentional practice.

Happiness is not just a feeling- its healthy! Joy and a positive attitude reduce stress, boost immunity, and enhance emotional resilience. Optimism and laughter trigger dopamine and serotonin release, promoting mental well-being, and reduce cortisol preventing stress-related illnesses. A joyful mindset strengthens social connections, is good for heart health, and increases longevity. It’s a vital part of a healthy life. 😊💛

To enhance happiness and resilience:

Practise kindness – Engage in small or meaningful acts of generosity.

Build social connections – Initiate conversations with strangers or deepen existing relationships.

Savour experiences – Fully immerse yourself in joyful moments.

Focus on the positive – Keep a journal of “Three Good Things” that happened each day.

Express gratitude – Write a letter to someone you never properly thanked.

Prioritise rest – Ensure sufficient sleep for mental and emotional resilience.

Remain active – Engage in regular physical movement to boost mood and energy.

Practise mindfulness – Cultivate present-moment awareness to reduce stress and enhance joy.

Hedonic and eudaimonic well-being.

Different forms of happiness exert different biological influence. Researchers distinguish between two forms of well-being:

Hedonic well-being (pleasure and immediate gratification).

Hedonic well-being comes from pleasure, self-gratification, and temporary joy. Enjoying sensory pleasures (such as food and relaxation), indulging in entertainment and social activities, seeking external validation (through praise or social media), and engaging in luxurious or comforting experiences (like shopping, vacations, and spa treatments) all provide instant gratification and relaxation, contributing to short-term happiness.

It is beneficial for mental health, but it has less impact on biological resilience compared to eudaimonic well-being.

Eudaimonic well-being (meaning and fulfillment).

Eudiamonic well-being comes from pursuing meaning, purpose, and contributing to others. Eudiamonia is the ancient Greek word for flourishing, frequently used as a synonyn of “happiness.” Finding deep fulfillment and purpose through helping others, pursuing passions and personal growth, building meaningful relationships, overcoming challenges, and engaging in purpose-driven work or family life fosters long-term well-being and resilience.

Biologically, it is associated with reduced inflammation, improved immune function, and better gene expression.

Live with purpose and meaning!

Higher eudaimonic well-being is associated with stronger immunity, lower inflammatory markers and better gene expression.

A. Hedonic well-being brings instant joy from pleasure, and self-gratification. It confers temporary joy.

B. Eudaimonic well-being promotes long-term fulfillment from pursuing meaning, purpose, and contributing to others.

Both are beneficial for mental health, but eudaimonic well-being has more impact on biological resilience compared to hedonic well-being.

A balanced life often includes both—the subject depicted enjoys hedonic pleasures, while also pursuing deeper meaning through service to the community.